Yolande Strengers, RMIT University and Larissa Nicholls, RMIT University

“Smart” home control devices promise to do many things, including helping households reduce their energy bills.

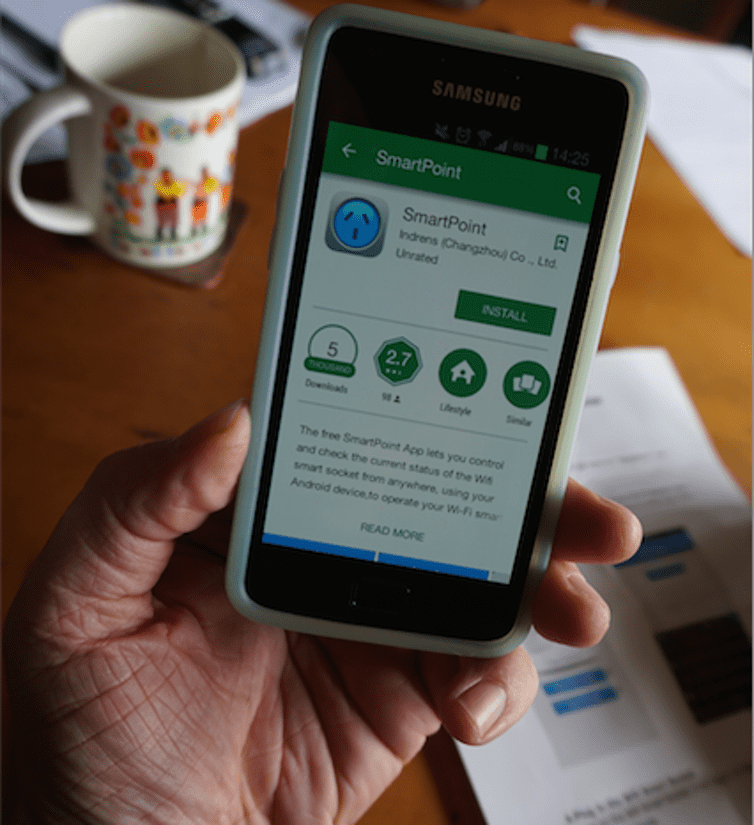

Devices such as “connected” lightbulbs and smart plugs let you operate or automate lights and other appliances from your smartphone, and are widely available from major retailers and online.

They are one of many innovative technologies advocated by the energy sector, and the recent Finkel Review of the energy market, to help consumers manage their energy use.

However, our research published today suggests that these devices are not the “easy” answer to energy management. In our trial, we found that households can use them in ways that increase energy use rather than reduce it, and that many people find them too complicated to get up and running.

Smart home techs on trial

In our study, funded by Energy Consumers Australia, we supplied 46 volunteer households in Victoria and South Australia with a couple of market-leading smart control devices to try out. We made sure we included a broad range of households – not just tech-savvy, early adopter types.

The results were surprising. A quarter of the households didn’t even attempt to install the devices; another quarter tried but failed to install them, and a further quarter successfully installed them but then abandoned them because they were considered inconvenient or not useful.

That left one quarter who were actively using the devices on an ongoing basis.

Unsuccessful installations weren’t just thwarted by the devices themselves or by a lack of persistence or knowledge. Householders who tried but gave up on the devices did so for a range of reasons, including smartphone compatibility issues, unreliable WiFi or Internet access, forgotten passwords, device app problems including recurring error messages, and concern over requests to hand over personal information.

Who used the devices?

The people most likely to successfully set up and continue using the devices were technology enthusiasts – and most often male. This is consistent with previous studies which have found that men are more likely to be interested in home automation.

Author provided

Energy-vulnerable households (those at higher risk of difficulty paying energy bills) were more interested in the devices than “regular” households, possibly because they placed greater value on the promised energy savings, or had more time to persist with the installation process. However, energy-vulnerable households are less likely to have the necessary technology infrastructure to use smart home control devices successfully, such as high-end smartphones and fast, reliable home internet connection.

Older participants in our study (those over 55) rarely used the devices. Households with children were concerned about the entry of more digital technology into their lives. Smart home control can also be inconvenient if some occupants continue to use the manual switches on lights or appliances (such as children without their own smartphones), as this can deactivate smart control for the rest of the household.

Lifestyle improvements beat energy savings

The households we interviewed were very interested in the potential for smart home control to improve their lifestyles, through improved security and safety, better comfort, conveniences such as turning lights off from bed, and aesthetic features such as “mood lighting”.

Yet while our study did not measure energy consumption, it was clear from the results that the ways households were using (or wanted to use) their devices could both decrease and increase energy consumption.

While some households reduced the operating time of lights or small appliances, others used smart control to increase their operating time, for instance by switching their heater on before getting home.

Pre-heating or pre-cooling homes, or running appliances when not at home to give the house a “lived-in” look intended to deter burglars, can be beneficial for health, comfort or well-being but can also increase energy consumption.

Tellingly, no household in our study used their smart devices to shift the timing of their energy use, even though most said their electricity rates were cheaper at night. When asked if smart plugs could help shift energy use to off-peak periods, many respondents said they did not see these devices as a necessary or convenient way to do it. They were more interested in simple timers and automation functions on the appliances themselves.

Doing more with smart home control

Six of the 46 households involved in our trial said they were interested in doing more with smart home control. However, they were mainly interested in lifestyle improvements rather than saving energy. This is consistent with the way these products are being marketed to households by technology companies.

Our findings are also consistent with another recent trial of smart home technologies in the UK. That study found that participants made either limited or no use of similar devices to manage their energy use. Like us, the research team raised concerns about the potential for smart control to generate new forms of energy demand.

These findings call for more caution in how smart home control is promoted by the energy sector. We need to be realistic about how these products are marketed, how the media influences the way the products are used, and how the other benefits of smart home control may affect home energy consumption.

The extent of technical and usability issues also needs to be acknowledged. There is a real risk that householders could spend considerable time and money on devices that don’t deliver energy savings. The devices are not equally accessible for everyone, and older users in particular might need help in using them effectively.

![]() The danger is in assuming that lower power bills can come neatly packaged in a box – the reality, as always, is more complicated.

The danger is in assuming that lower power bills can come neatly packaged in a box – the reality, as always, is more complicated.

Yolande Strengers, Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University and Larissa Nicholls, Research Fellow, RMIT University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.